Chapter 1 : The Port of Beginnings

I recall still the fishy smell and salt that clung to the air like a second skin. The sea wind blew through San Telmo’s twisted streets, that smoke and steam port town where the ships loomed like castles on the horizon. Here, in the grime and glory of the docks, I first laid eyes on destiny. Not in the stars above, nor in a monk’s scroll’s script—but in the timbered hold of the ship bound for the world’s edge.

I was born without a name worthy of being borne and without a coin to give for luck. Diego, they called me—just Diego. The priests told me I was discovered on the morning of San Sebastian’s Abbey one winter morning, wrapped in a blood-drenched shawl. No parents. No lineage. Just a name that the old midwife spoke out and handed me off like some package of sin.

I was raised amidst the silent stone walls and candlelit prayers of the monastery, sweeping floors and bearing water, learning to read from old Father Ignacio, who said that I had the eyes of a wanderer and the heart of a fool. I believed him. For while the other boys prayed to be scribes or priests, I’d sit by the tower window and watch the sails in the distance and dream of lands I could not name.

At twenty, the abbey could no longer hold me. My hands were too calloused, my questions too arrogant. They gave me a loaf of bread, a cloth-wrapped coin, and the cross. I took all and followed east along the shore on roads etched by merchants and mercenaries, by thieves and pilgrims. Three days hence, I arrived in San Telmo.

The city was nothing like I was accustomed to. Stony houses tilted over the narrow streets like a covey of whispering elderly women. Market stalls bellowed in ten tongues, selling anything from silks and spices to dirty baubles and monkey bones. Sword-wielding men with secrets in their eyes strode on past. And above, the harbor loomed—lined with ships the size of cathedrals, each creaking with the potential of somewhere else.

I paid for a room in a crooked tavern overlooking the water with my final coin, washing with a bath of straw and a dish of lentils. The owner, an old man, looked at me like a famished cur but said nothing. I spent the next day walking the wharves, inquiring of every master of a ship if he needed hands. Most laughed. Some shooed me away. A few cursed in words I could not recognize.

Then the evening tide came.

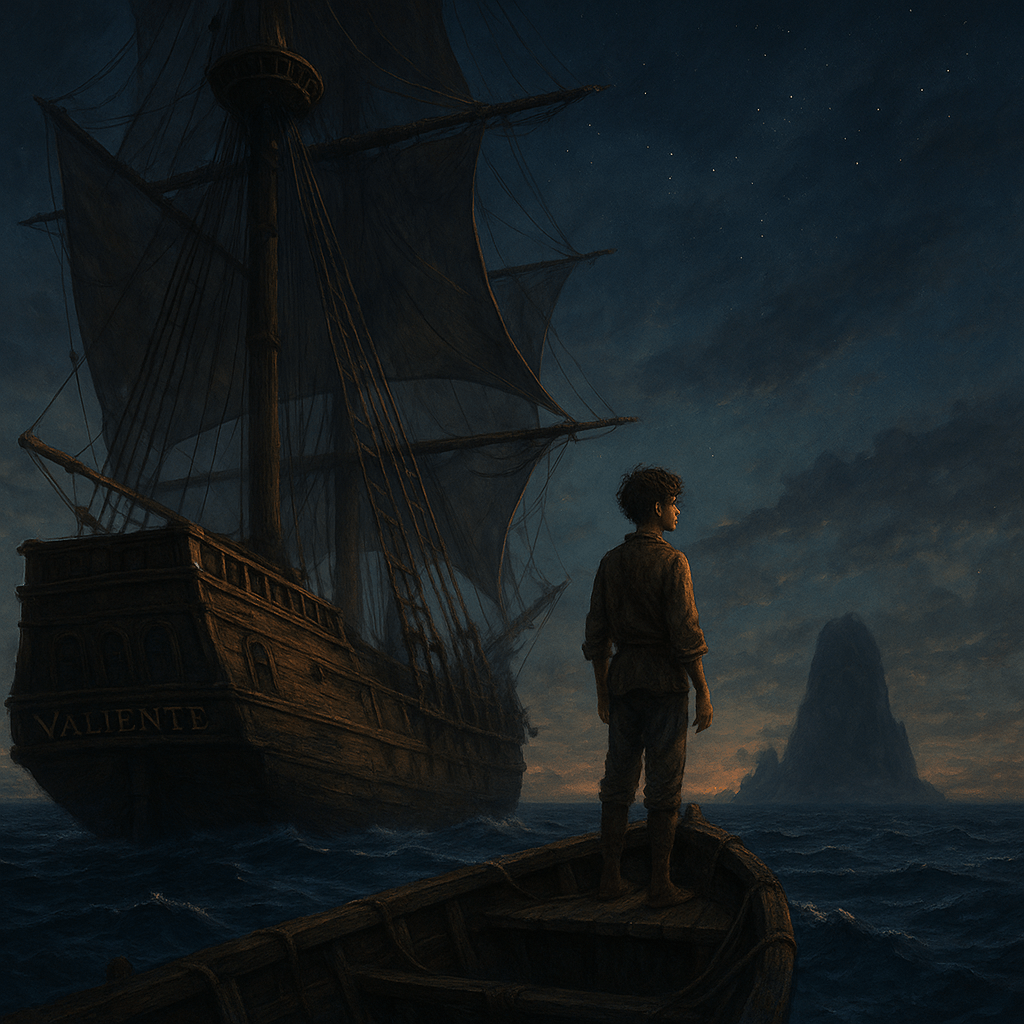

I sat astride a stack of crates, hope worn thinner than the leather of my boots, when I saw her—the Valiente. She was not a typical vessel. Her hull bore wounds from distant storms, and her sails, though mended, puffed with a defiant spirit. Men clung to her deck like bees on a dying bloom. One man stood tall among them, a voice of thunder as he yelled commands.

He wore a red leather greatcoat and a tri-corner hat, though the fashion had not yet reached Spain. There was a scar from his left eyebrow to his cheek, over an eye that burned like gold in the fading light. Captain Rodrigo Navarro, they called him. I found that name drawn in both fear and awe from Lisbon to Alexandria.

I’m not sure why I stepped forward, or why I raised my hand and bellowed, “I seek passage, Captain. I can work.”

The circle of men around him fell silent. The captain turned to me, looked at me as if estimating the depth of my soul, and motioned me forward.

“You’ve got bones,” he grated, his voice a rough mixture of gravel and rum. “But can you haul sail, scrub deck, climb mast, and bleed without crying?”

I can learn,” I said to him.

He scowled his good eye. “Name?”

“Diego.”

He snarled. “No surname?”

“No family.”

“A bastard, then,” he muttered. “Good. No one to mourn you.”

He turned to a man standing beside him. “Put him with the deckhands. If he gets through the week, we’ll keep him.”

And like that, I was on board.

The Valiente departed three days later, their decks under the fiery color of a blood-orange sky. They gave me rope-scalded gloves and a hammock hung between two rum barrels. I learned quickly. Learned how to tie knots that would last through a storm, how to scale ropes when the wind screamed, how to sleep with an eye open and never trust anyone with two.

The sea was cruel, yes. But it was also free. And in its enormous, uncaring heart, I found something the abbey had never given me: purpose.

I was no longer just Diego, the orphan. I was Diego of the Valiente.

And I had only just begun.

My first night on the Valiente, I lay awake. The groan of the wooden hull, the complaint of ropes above, and the rhythmic thud of boots on the deck all combined to make it clear that I was no longer on land—and definitely not in the solitary stillness of the abbey. Noises were louder, more alive. And the scent of sweat, pitch, and sea brine hung over everything.

I lay in my hammock staring into the dark, swaying gently to the roll of the ship, listening to men snore and speak in their sleep—French, Arabic, Castilian, even one northerner who murmured in what sounded like birdsong. I knew then that I was among men who had traveled from countries I’d never visited, who had stories I couldn’t conceive of.

By dawn, we were well off the coast. Land was a line on the horizon. I had never been out of sight of land before. It was beautiful. And it was terrifying.

The crew wasted no time in reminding me of my place.

“Orphan boy,” they called me, and worse. I was set to scrubbing the deck with salt water, swabbing the latrines, and hauling buckets of bilge water until my arms screamed. I kept my head down. I watched. I learned.

There was Mateo, a barrel-chested Moor with arms as thick as tree trunks who taught me to tie a bowline knot blindfolded. There was Old Javi, a tall, thin Galician chef who once cooked for nobles and now spat their names as he stirred stews of questionable origin. And there was Luca, the youngest until I arrived, a Sicilian with thin eyes and a thinner tongue. He teased me relentlessly—until I beat him in a rope-climb contest one rainy morning. We didn’t speak after that. We didn’t have to.

The captain, Navarro, was a distant storm cloud. He did not speak much, but when he did, all men heard him. There were whispers about him like seagulls over a corpse. Some said he had once burned an entire Ottoman galley for stealing his charts. Others said he pursued ghosts along the African coast. Whatever the truth was, even the first mate, a pale man named Álvaro with fingers stained with ink, bowed his head when Navarro passed.

One morning, three weeks into our voyage, Álvaro called me up to the quarterdeck.

“Você pode ler?” he asked, waving a scroll.

“Yes,” I said.

He handed it to me. “Translate this. Latin to Castilian.”

It was a map. An old one. Faded lines, symbols marked in unusual ink. I translated the markings slowly, recalling my days at the abbey, the hours I’d spent copying scriptures and charts by candlelight.

When I finished, Álvaro nodded seldom. “The captain was correct.”

“Correct about what?”

“That you’re not here to haul buckets only.”

He said no more. But from that day, I was summoned now and then to help him read charts and journals. I still did deck work, still ate stale bread and fish bones with the rest—but a change had begun.

I started to know things no one taught.

We weren’t just trading goods.

We were looking for something.

There were rumors, always spoken in the nighttime. Rumors of unseen lands, of golden cities deep in the jungles beyond the sea, of relics the Church had long interred. I heard the name “Tartessos” more than once—a long-lost kingdom that was rumored to have sunk into the ground, devoured by greed or the gods.

And there were the stars.

Each evening, Captain Navarro would pace the prow, gazing up at the constellations with a kind of longing. He kept a brass astrolabe, lovelier than any device I’d ever seen, and spoke to it as a priest speaks to a relic.

One evening, when I came down from the rigging after a storm, he caught me staring.

“Do you believe in fate, boy?” he asked, without turning around.

“I don’t know.”

He smiled faintly. “That’s the right answer.”

He glanced up at the stars again. “They say if you travel west far enough, you come to the end of the world. Water turns to fire. The ocean falls off into nothing.”

“Do you believe that?”

“I believe men create such tales so they do not have to make that journey.”

There was a silence between us. The waves were still now, but the wind carried the chill of something ancient.

“Why are we going west?” I dared to ask.

Navarro did not answer at once. Then he turned to me.

“To look for something the popes and kings would kill for,” he said. “But they’re afraid to look.”.

He turned away after that, his coat billowing behind him like a flag in the wind. I remained standing long after he was gone, heart racing—not with fear, but something even more dangerous: curiosity.

By the time a month went by, I no longer felt a stranger on the Valiente. I had my scars, my bruises, and the sea had entered my bones. I had bled for this ship, cursed her, praised her. And I was no longer at the bottom of the crew’s ranks.

But the sea—she never lets you forget who is in charge.

It sounded just before dawn. A shriek from the crow’s nest. The bell rang out. Men scrambled to their stations. The sails dipped like wounded birds. I ran along with the others, my heart pounding.

A shape took form on the horizon. Black. Massive. We thought at first it was a rock.

Then it moved.