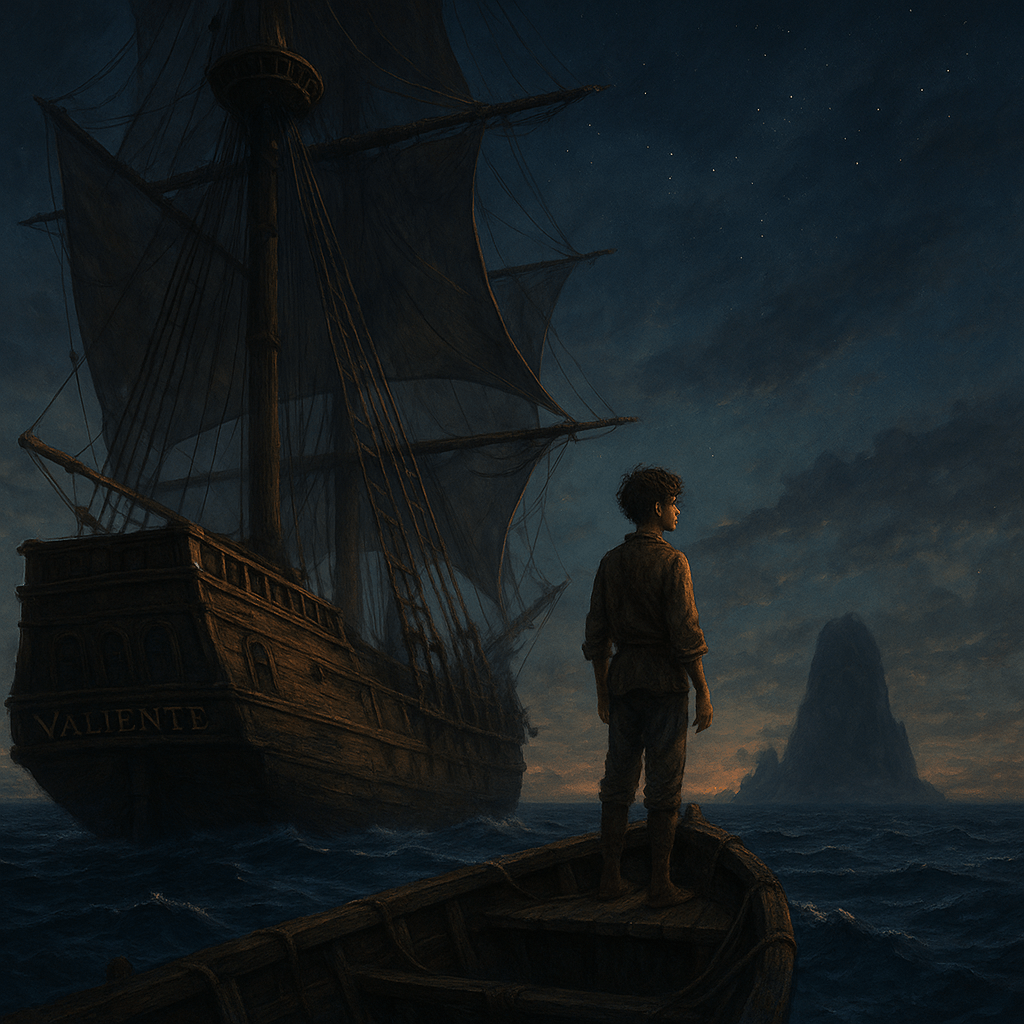

Chapter 1 : The Port of Beginnings I recall still the fishy smell and salt that clung to the air like a second skin. The sea wind blew through San Telmo’s twisted streets, that smoke and steam port town where the ships loomed like castles on the horizon. Here, in the grime and glory of the docks, I first laid eyes on destiny. Not in the stars above, nor in a monk’s scroll’s script—but in the timbered hold of the ship bound for the world’s edge. I was born without a name worthy of being borne and without a coin to give for luck. Diego, they called me—just Diego. The priests told me I was discovered on the morning of San Sebastian’s Abbey one winter morning, wrapped in a blood-drenched shawl. No parents. No lineage. Just a name that the old midwife spoke out and handed me off like some package of sin. I was raised amidst the silent stone walls and candlelit prayers of the monastery, sweeping floors and bearing water, learning to read from old Father Ignacio, who said that I had the eyes of a wanderer and the heart of a fool. I believed him. For while the other boys prayed to be scribes or priests, I’d sit by the tower window and watch the sails in the distance and dream of lands I could not name. At twenty, the abbey could no longer hold me. My hands were too calloused, my questions too arrogant. They gave me a loaf of bread, a cloth-wrapped coin, and the cross. I took all and followed east along the shore on roads etched by merchants and mercenaries, by thieves and pilgrims. Three days hence, I arrived in San Telmo. The city was nothing like I was accustomed to. Stony houses tilted over the narrow streets like a covey of whispering elderly women. Market stalls bellowed in ten tongues, selling anything from silks and spices to dirty baubles and monkey bones. Sword-wielding men with secrets in their eyes strode on past. And above, the harbor loomed—lined with ships the size of cathedrals, each creaking with the potential of somewhere else. I paid for a room in a crooked tavern overlooking the water with my final coin, washing with a bath of straw and a dish of lentils. The owner, an old man, looked at me like a famished cur but said nothing. I spent the next day walking the wharves, inquiring of every master of a ship if he needed hands. Most laughed. Some shooed me away. A few cursed in words I could not recognize. Then the evening tide came. I sat astride a stack of crates, hope worn thinner than the leather of my boots, when I saw her—the Valiente. She was not a typical vessel. Her hull bore wounds from distant storms, and her sails, though mended, puffed with a defiant spirit. Men clung to her deck like bees on a dying bloom. One man stood tall among them, a voice of thunder as he yelled commands. He wore a red leather greatcoat and a tri-corner hat, though the fashion had not yet reached Spain. There was a scar from his left eyebrow to his cheek, over an eye that burned like gold in the fading light. Captain Rodrigo Navarro, they called him. I found that name drawn in both fear and awe from Lisbon to Alexandria. I’m not sure why I stepped forward, or why I raised my hand and bellowed, “I seek passage, Captain. I can work.” The circle of men around him fell silent. The captain turned to me, looked at me as if estimating the depth of my soul, and motioned me forward. “You’ve got bones,” he grated, his voice a rough mixture of gravel and rum. “But can you haul sail, scrub deck, climb mast, and bleed without crying?” I can learn,” I said to him. He scowled his good eye. “Name?” “Diego.” He snarled. “No surname?” “No family.” “A bastard, then,” he muttered. “Good. No one to mourn you.” He turned to a man standing beside him. “Put him with the deckhands. If he gets through the week, we’ll keep him.” And like that, I was on board. The Valiente departed three days later, their decks under the fiery color of a blood-orange sky. They gave me rope-scalded gloves and a hammock hung between two rum barrels. I learned quickly. Learned how to tie knots that would last through a storm, how to scale ropes when the wind screamed, how to sleep with an eye open and never trust anyone with two. The sea was cruel, yes. But it was also free. And in its enormous, uncaring heart, I found something the abbey had never given me: purpose. I was no longer just Diego, the orphan. I was Diego of the Valiente. And I had only just begun. My first night on the Valiente, I lay awake. The groan of the wooden hull, the complaint of ropes above, and the rhythmic thud of boots on the deck all combined to make it clear that I was no longer on land—and definitely not in the solitary stillness of the abbey. Noises were louder, more alive. And the scent of sweat, pitch, and sea brine hung over everything. I lay in my hammock staring into the dark, swaying gently to the roll of the ship, listening to men snore and speak in their sleep—French, Arabic, Castilian, even one northerner who murmured in what sounded like birdsong. I knew then that I was among men who had traveled from countries I’d never visited, who had stories I couldn’t conceive of. By dawn, we were well off the coast. Land was a line on the horizon. I had never been out of sight of land before. It was beautiful. And it was terrifying. The crew wasted no time in reminding me of my place. “Orphan boy,” they called me, and worse. I was set to